* * * Click covers for links * * *

Cup of dreams

Walking past the temple

Mapping Simon

Here’s the passage in Alice that follows the full moon gathering.

xxx

“What are you doing?” asked Alice.

Christopher looked up from his task. He was in Alice and Evelyn’s garden, crouched between a row of cabbages and a row of fine hot serrano peppers. Fairies hummed in the not-too-distant woods and ladybugs flitted unobtrusively. Lying in the rut between the rows was Simon, his small deformed body naked to the sun and the sky and the sportive play of bugs. He was face down, but his gargantuan hands, his uneven buttocks and bowling ball head, all indicated restfulness.

“I’m mapping Simon,” Christopher said.

“Look at him,” said Alice. Then she leaned over and kissed Christopher on the lips.

“You have such a way of putting people at ease,” Alice said. “Sometimes I think your thing isn’t mapmaking but putting people at ease.”

Christopher went back to work with his tools and widgets.

“Why are you mapping Simon anyway?” Alice asked.

“John Wilson asked me to,” said Christopher.

Interesting, thought Alice. John Wilson never asked for anyone to be mapped before. He mainly just ran things, walked around and got input from the different New Arcadians, and then ran things some more. Why does he want Christopher to map Simon?

She received a clue to this mystery later that afternoon. Simon had come in and was in a warm bath. Christopher had gone into the room with Evelyn to rub her legs and possibly make love. And TOCK-TOCK-TOCK, John Wilson was at the door.

“Come in, John Wilson,” said Alice. “Why did you want Christopher to map Simon?”

“I don’t trust Simon,” said John Wilson. “Where did he come from and why? No one seems to ask the right questions around here.”

John Wilson seemed irritated, which amused Alice. Of course, he was right. No one knew where Simon had come from or why. It might be good to find these things out.

Later, after Christopher had returned to Freyda the white witch and John Wilson had returned to his live-in wing behind the communal hall, Alice lay in Evelyn’s arms enjoying the night – the smells in the window, the hum of fairies and other sounds of small birds and animals. Simon was sleeping on the box in the corner of the bedroom where she had propped him up. Where was he from? And why was he here? Where was he from? And why was he here? Where was he from?

She must have fallen asleep like her namesake who went through the looking-glass, because soon it wasn’t her asking the two questions, but a figure in the darkest corner of the room, a hooded figure, sitting in an old rocking chair that had come down to Alice from God knows when.

xxx

Ok, that’s enough for now. Just click the cover and buy the book before it’s too late.

* * * Click covers for links * * *

Shibuya Crossing and a Close Call

Up to 3000 people cross on a single walk sign at Shibuya Crossing, the world’s busiest pedestrian crosswalk.

For comparison, note that for about 100,000 years (roughly 900,000 to 800,000 years ago), the entire population of our human ancestors was reduced to about half that. I’d say that’s a close call.

* * * Click covers for links * * *

Isolation and connection

We are thrown into the world with no rhyme or reason, say Martin Heidegger (Being and Time) and the existentialists. Presumably, this arbitrary and inscrutable “thrownness” is a big source of the anxiety and isolation that condition our existence. Gloomy lot, these existentialists.

But is there an antidote to the gloom? If so, maybe it comes from hippie philosopher par excellence, Alan Watts. The idea that we “come into the world” as “isolated egos .. who confront an external world of people and things, making contact through the senses with a universe both alien and strange” — all of that is a hallucination, says Watts. And we can dissolve the hallucination with one simple fact: “We do not ‘come into’ this world; we come out of it, as leaves from a tree” (The Book).

* * * Click covers for links * * *

So much depends upon

Image from melo03.wordpress.com/2010/01/13/william-carlos-williams-the-red-wheelbarrow.

so much to say

about

a simple

image

glazed with something

more

despite the old

poet

* * * Click covers for links * * *

NOMA in the trees

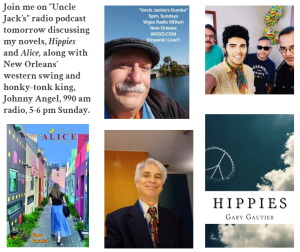

Uncle Jack’s discussion

For the radio podcast to go with the image of yesterday’s post per my novels, Hippies and Alice, click HERE. My bit is at 15:30-24:00 😊

* * * Click covers for links * * *